« Food Commons v2 » : différence entre les versions

Aucun résumé des modifications |

Aucun résumé des modifications |

||

| (Une version intermédiaire par le même utilisateur non affichée) | |||

| Ligne 270 : | Ligne 270 : | ||

'''(b) The Partner State governing food as a public good''' | '''(b) The Partner State governing food as a public good''' | ||

The state has as its main goals the maximisation of the well-being of its citizens and will need to provide an enabling framework for the commons. The transition towards a food commons regime will need a different kind of state (national states and EU authorities), with different duties and skills to steer that transition. The desirable functions are shaped by partnering and innovation rather than command-and-control via policies, subsidies, regulations and the use of force. This enabling state would be in line with Karl Polanyi’s (1944) theory of its role as shaper and creator of markets and facilitator for civic collective actions to flourish. This state has been called Partner State (Kostakis & Bauwens, 2014) and Entrepreneurial State (Mazzucato, 2013). The partner state has public authorities as playing a sustaining role (enabling and empowering) in the direct creation by civil society of common value for the common good. Unlike the Leviathan paradigm of top-down enforcement, this type of state sustains and promotes commons-based peer-to-peer production. Amongst the duties of the partner state, Silke | The state has as its main goals the maximisation of the well-being of its citizens and will need to provide an enabling framework for the commons. The transition towards a food commons regime will need a different kind of state (national states and EU authorities), with different duties and skills to steer that transition. The desirable functions are shaped by partnering and innovation rather than command-and-control via policies, subsidies, regulations and the use of force. This enabling state would be in line with Karl Polanyi’s (1944) theory of its role as shaper and creator of markets and facilitator for civic collective actions to flourish. This state has been called Partner State (Kostakis & Bauwens, 2014) and Entrepreneurial State (Mazzucato, 2013). The partner state has public authorities as playing a sustaining role (enabling and empowering) in the direct creation by civil society of common value for the common good. Unlike the Leviathan paradigm of top-down enforcement, this type of state sustains and promotes commons-based peer-to-peer production. Amongst the duties of the partner state, HELFRICH Silke mentioned the prevention of enclosures, triggering of the production/construction of new commons, co-management of complex resource systems that are not limited to local boundaries or specific communities, oversight of rules and charts, care for the commons (as mediator or judge) and initiator or provider of incentives and enabling legal frameworks for commoners governing their commons. The entrepreneurial state, meanwhile, fosters and funds social and technical innovations that benefit humanity as public ideas that shape markets (such as, in recent years, the Internet, Wi-Fi, GPS), funding the scaling up of sustainable consumption (like the Big Lottery Fund supporting innovative community food enterprises that are driving a sustainable food transition in UK) and developing open material and non-material resources (knowledge) for the common good of human societies. Public authorities will need to play a leading role in support of existing commons and the creation of new commons for their societal value. | ||

'''(c) The non-profit maximiser Private Sector''' | '''(c) The non-profit maximiser Private Sector''' | ||

| Ligne 460 : | Ligne 460 : | ||

<references /> | <references /> | ||

[[Fait partie de::European Commons Assembly/Policy Proposals]] | |||

Dernière version du 2 avril 2018 à 18:18

The Food Commons in Europe:

relevance, challenges and ideas to feed them

1.- BACKGROUND AND RATIONALE

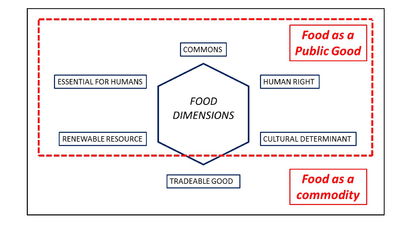

Food, a life enabler and a cultural cornerstone, is a resource with multiple meanings and different valuations for societies and individuals. Food shapes morals and norms, triggers enjoyment and social life, substantiate art and culture (gastronomy), affects traditions and identity, relates to animal ethics and determines and is shaped by power and control. Therefore, this multiple and relevant meanings cannot be reduced to the one of tradeable good. The value of food cannot be fully expressed by its price in the market. The six dimensions of food (see figure below), namely food as an essential life enabler, a natural resource, a human right, a cultural determinant, a tradeable good and a commons, cannot be reduced to the mono-dimensional valuation of food as a commodity. So far, the theory of the commons has barely touched upon food, still considered a realm that escapes the normative doctrine and praxis of commoners and common scholars. Oddly enough, the different epistemologies (schools of thought) that have analysed the commons in order to understand its nature, origins, governance, utilities and challenges have rarely considered that food is a commons or can function as a commons.

In this proposal, we understand the author subscribes the political understanding of the commons, namely the consideration of commons as a phenomenological regard or a social construct that depends on the collectively-arranged form of governance for any particular resource, material or immaterial, in a situated place and time. The resources considered and governed as commons are usually those that are deemed important for the society, and hence its governance, production and utilisation has to be done in common. The commons are thus not defined by the ontological properties intrinsic to the goods, but rather by its collective governing decision and the essentiality of the resource governed as a commons to everyone. Summing up the idea in a simple definition of the commons “the resource plus the commoning”. It is commoning together what confers a material and non-material common resource its commons consideration. The consideration of food as a commons rests upon its essentialness as human life enabler and the multiple governing arrangements that have been set up across the world and historical periods to produce and consume food, outside market mechanisms. Moreover, a food commons means revalorising the different food dimensions (see figure) that are relevant to human beings (value-in use) and thus reducing the tradable dimension (value-in exchange) that has rendered it a mere commodity. A regime based on food as a commons would inform an essentially democratic food system (food democracy) based on sustainable agricultural practices (agro-ecology) and open-source knowledge (creative commons licenses) through the assumption of relevant knowledge (cuisine recipes, agrarian practices, public research), material items (seeds, fish stocks, land, forests, water) and abstract entities (transboundary food safety regulations, public nutrition) as global commons.

2.- TYPOLOGY OF THE FOOD COMMONS

1.- Food shall be considered a commons (a social construct that the European peoples can agree upon) based on its essentialness for human survival and the commoning practices that different peoples are maintaining (customary) or inventing (contemporary) to produce food for all, based on a rationale and ethos different from the for-profit capitalistic one.

2.- There are material components of food commons (natural and cultivated food stuff) and non-material components such as agricultural knowledge or cooking recipes.

3.- The food-producing commons (agricultural systems, seafruit collection, fishing, hunting and wild gathering) can be governed themselves as commons, as it actually happens in many places of Europe. Those food-producing commons can classified as customary and contemporary, with heritage and history being the main cleavage although they share values, institutions, priorities and forms of governance.

4.- Customary Food-producing Commons (land-based, mostly rural, ICCAs[2], resisting commodification)

The natural resources are mostly owned in collective proprietary regimes, with different right entitlements (bundles of rights). They are located in rural Europe (lower incomes, poor connectivity, low densities), associated to cultural heritage, landscape preservation and biodiversity stewardship. Directly affected by CAP policies, Natura 2000 directives and food safety regulations. They are resisting the privatisation and enclosing waves triggered by capitalism, consumerism and individualism.

5.- Contemporary Food-producing Commons (community-based, mostly urban, innovating practices)

They are mostly urban led, or rur-urban located, formed by innovative and disruptive initiatives that re-invent traditional methods of governing commons (community housing, community gardens) or design new commons that did not exist before, using internet, communication technologies and hyper-connectivity.

3.- THE CHALLENGES

Food is treated as a mere commodity in European policies, legal frameworks and normative views. Food is not considered as a human right in EU charters, constitutions and legal frameworks (Vivero-Pol & Schuftan, 2016)), nor a public good subject to public policies and universal access (such as health, education or water) and least to say a commons, although many commons and community-owned resources are producing food for Europeans (Vivero-Pol, forthcoming and ICCAS country studies for Euroe). The Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) basically deals with food as a for-profit commodity that is exclusively governed through market mechanisms, and public food policies are mostly geared to facilitate that market and to subsidise big food producers of the industrial food system. None of the five relevant regulations of the reformed CAP (December 2013) include any mention to “commons”, “common resources” or the “right to food”. The food-producing commons do not exist in the Common Agricultural Policy.

The consideration of food as a commodity and the widespread belief that only through profit-driven market mechanisms can food be produced and distributed is pervasive in European policies and institutions. As a token, a recent foresight report on the global food security by 2030 (Maggio et al., 2015) considers food as “an opportunity for trade, innovation, health, wealth & geopolitics” (p.34) with no single mention to food as vital need, a human right or a cultural determinant for Europeans.

The European industrial food system and its many externalities (climate change, disappearance of small-farming, unhealthy ultra-processed food, food waste, unfair prices to producers, the absence of the right to food, subsidies diverted to corporations and bigger farmers, water and soil pollution, biodiversity reduction, etc) are driven by the valuation of food as a commodity and the ethos of profit maximising. The Common Agricultural Policy does not consider food or food systems as a commons, despite the myriad of positive services the agricultural systems provide to European peoples.

Moreover, the European industrial food system is not even more efficient or cost-benefit than the more sustainable food systems (either modern organic or customary) as it is heavily subsidized and amply favoured by tax exemptions[3]. The great bulk of national agricultural subsidies in OECD countries are mostly geared towards supporting this large-scale industrial agriculture[4] that makes intensive use of chemical inputs and energy (Nemes, 2013), and that helps corporations lower the price of processed food compared to fresh fruits and vegetables. The alternative organic systems are more productive, both agronomically and economically, more energy efficient and they have a lower year-to-year variability (Smolik et al., 1995) and they depend less on government payments for their profitability (Diebel et al., 1995).

Anyhow, it is not about “organic” vs. “industrial” agriculture, it is about valuing the multiple dimensions of food to human beings other than its artificially-low price in the market. For instance, dimensions related to fair production and nutritional and enjoyable consumption, compared to the mono-dimensional approach to food as a commodity, where the major driver for agri-businesses is to maximize profit by producing and delivering cheap food with low nutritional value and high-energy demanding.

In parallel to the enclosure of food-producing commons (land, seeds, water and agricultural knowledge), food evolved from a common local resource to a private transnational commodity, becoming an industry and a market of mass consumption in the globalized world (Fischler, 2011). This process ended up in the dominant industrial system that fully controls international food trade and, although it does not even feed 30% of the global population, has given rise to the corporate control of life-supporting industries, from land and water-grabbing to agricultural fuel-based inputs.

Food Insecurity is rising in Europe with this dominant narrative of food as a commodity: Food Insecurity (understood as the unability to eat meat every second day) is already affecting 13.5 M people (10.9%) with a 2.7% increase since austerity measures were implemented; there 30 M malnourished people in Europe according to the Transmango Research project; 50 M people with severe material deprivation including food and water (EUROSTAT, 2015) and 30-40% children in 6 EU countries are below poverty line (UNICEF, 2014).

Table 1: Legal and political features of basic needs and their entitlements in Spain

| Human Right status | Constitutional Right status | Universal Coverage Scheme | Public Good consideration (with mixed or public governance) | Commodification process | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Ongoing (advanced) |

| Education | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Ongoing (beginning) |

| Sanitation | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No |

| Water | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Ongoing (beginning) |

| Food | yes | No | No | No | Fully achieved |

In this scenario of rising food insecurity in Europe, food is not even considered as an enforceable human right in the EU legal frameworks or the national legal frameworks of the EU members. As an enlightening example that may illustrate this mono-dimensional valuation, table 1 below shows the different political constructs applied to specific basic needs in Spain. Health, education and water are human rights enshrined in the Constitution and enjoying a political consideration of public goods, where the universal access to them is guaranteed by the State to every Spaniard (although this consideration is under threat by the privatisation measures triggered by the austerity ideology). However, food is the only basic need that do not enjoy neither the category of enforceable human right, nor the consideration of public good where all should have universal access to that vital resource. It is provision is left to market forces that are only interested in producing cheap food with environmental consequences for those who are capable of paying the price. Food is neither a right, nor a public good or a commons in Spain. Just a commodity.

4.- EXISTING EXPERIENCES OF FOOD COMMONS IN EUROPE

Forests, fisheries, land, water and food have all been considered as commons and the consideration different civilisations have assigned to food-producing commons is rather diverse and certainly evolving. Food-producing commons are ubiquitous in the world, largely based on their abundance in historical times and the fact that different past and present enclosing movements have not been able to make them disappear…yet. History records are full of commons-based food production systems ranging from the early Babylonian Empire (Renger, 1995), ancient India (Gopal, 1961) and Medieval Europe (Linebaugh, 2008) to early modern Japan (Brown, 2011).

In Europe, despite centuries of encroachments, misappropriations and legal privatizations, more than 12 Million hectares of common lands have survived up to now in many EU countries[5]. This figure is estimative since it includes only 13 EU member states and only refers to Utilised Agriculture Area (area used for farming). Forested or coastal areas are not include, what will certainly raise the figure.

| MEMBER STATE | COMMON LAND (ha) year 2010 |

| Spain | 4 205 593 |

| Cyprus | 805 |

| France | 750 000 |

| Ireland | 422 415 |

| Italy | 610 165 |

| Austria | 252 872 |

| Portugal | 171 351 |

| United Kingdom | 1 195 246 |

| Hungary | 627 225 |

| Bulgaria | 858 563 |

| Romania | 1 497 764 |

| Greece | 1 698 949 |

| Slovenia | 8 221 |

| Norway | Unknown |

| Croatia | Not identified |

| Montenegro | Not identified |

| EU TOTAL (ha) | 12 299 265 |

The extension of the commons in the EU is not known with any precision, but the European Commision estimates in more than 12 million hectareas the Utilised Agriculture Area (UAA) (meaning the area used for farming) under common land (data do not include forestry or marine areas)

Source: European Commission. Eurostat.

In highly privatized and increasingly neoliberal Western Europe, common lands still cover 9% of surface of France (Vivier, 2002), more than 10% in Switzerland and 25% of Galicia (in Spain). Anyone can forage wild mushrooms and berries in the Scandinavian countries under the consuetudinary Everyman’s Rights[6] (La Mela, 2014; Mortazavi, 1997), the Spanish irrigated huertas (vegetable gardens) are a well-known and healthy institution (Ostrom, 1990, pp 69-81) and there are thousands of surviving community-owned forests and pasturelands in Europe where livestock are raised in free-range, namely Baldios in Portugal (Rodrigues, 1987), Crofts in Scotland or Montes Vecinales en Mano Comun in Spain (Grupo Montes Vecinales IDEGA, 2013).

In United Kingdom, common lands are a mix of use rights to private property and commonly-owned lands[7]. Local residents (called commoners) have often some rights over private land in their area[8]. Most commons are based on long-held traditions or customary rights, which pre-date statute law laid down by democratic Parliaments. The latest data indicate England has circa 400.000 ha (3%) registered as common land[9], Wales 175.000 ha (8.4%) and Scotland 157.000 ha (2%), what amounts 732.000 ha representing at least 3.3% of United Kingdom[10]. Common lands in Spain, those owned by communities and not being part of state-owned territory, are 4.2% (2.1 million ha) according to the most accurate agrarian census. These lands, with more than 6600 farming households that depend entirely on them for earning their living, are grounded on legal principles that ensure the preservation of the communal condition of such property, as they cannot be sold (unalienable), split into smaller units (indivisible), donated or seized (non-impoundable) and cannot be converted into private property just because of their continued occupation (non-expiring legal consideration) (Lana-Berasain & Iriarte-Goni, in press). The 1978 Constitution (Article 132/1) included an explicit reference to the commons, also defined in the Municipal Law of 1985. Ownership corresponds to the municipality or commonality of the neighbours and its use and enjoyment to the residents.

In Galicia, an autonomous region of Spain, common lands represents 22.7% of total surface and they are owned and managed by resident neighbours[11] inhabiting visigothic-based parishes[12], a legal figure recognized in the 1968, 1989 and 2012 laws[13] (Grupo Montes Vecinales IDEGA, 2013). Finally, in the medieval village of Sacrofano (Roma province, Italy), a particular and ancient University still functions for the local residents: the Agricultural University of Sacrofano[14] (Università Agraria di Sacrofano) holds 330 ha of fields, pastures, forests and abandoned lands where the citizens residing in the municipality can exercise the so-called rights of civic use (customary rights to use the common lands).

Those are just a few documented examples of the socio-economic importance of the food-producing commons in Europe although its relevance and current existence is hardly noticed by general media and probably neglected by the public authorities and the mainstream scientific research. Historical and modern studies have shown that the traditional food-producing common-pool resources systems were, and still are, efficient in terms of resource management[15] as can be seen from their coherence and persistence despite the different enclosing waves (Ostrom, 1990; De Moor et al. 2002). Common lands were pivotal for small farming agriculture throughout Europe all along history, as they were source of organic manure, livestock feedstock and pastures, cereals (mostly wheat and rye in temporary fields), medicinal plants and wood. Peasants pooled their individual holdings into open fields that were jointly cultivated, and common pastures were used to graze their animals. Their utility to human societies enabled them to survive up to present day.

In Europe there still are many examples of customary food commons that are functional, providing food to many communities and stewarding natural resources and cultures. Some examples can be provided by the irrigation system in the Huertas of Valencia, the emphiteusis proprietary regimes in Italy, the management of oyster beds in the Arcachon bay, the pastoral traditions of Sami people in the Scandinavian countries, the hunting licences in Switzerland and so on, so forth. A couple of rather different examples from a traditional food commons and an innovative new one can be found below:

Customary Food Commons: “Caffe sospeso” (Italy). A tradition that began in the working-class cafés of Naples, where someone who had experienced good luck would order a “sospeso”, paying the price of two coffees but receiving and consuming only one. A poor person enquiring later whether there was a “sospeso” available would then be served a coffee for free. Although this customary tradition was almost gone in Naples, it is being re-invigorated in other places (i.e. US, Spain) by contemporary food initiatives (Buscemi, 2015).

Contemporary Food Commons: These type of social innovations are mushrooming in the XXI century, particularly since the 2008 food crisis hit the news and we all felt their impacts in food prices and political agendas. Numerous examples can be found in European urban and rural areas, such as Ecovillages[16] and Transition Towns[17]

Global Eco-village Network Europe[18]. An ecovillage is a human-scale settlement consciously designed through participatory processes to secure long-term sustainability. All four dimensions (the economic, ecological, social and cultural) are seen as mutually reinforcing. ECOLISE (European Network of Community Led-Initiative on Climate-change and Sustainability)[19] is a coalition of organisations engaged in promoting and supporting local communities across Europe in their efforts to build pathways to a sustainable future. This re-localisation and re-appropriation of spheres of life that are important at community/local level includes many types of commons which are owned and managed by the community such as community gardens, energy facilities, community supported agriculture, shared mobility schemes, direct democracy, open administration, etc. We are connected to the practical aspects of communing; we explore ways to live in common that are not based only on personal property and individual actions. The trend is to create collective properties and local community actions.

Transition Networks is a placed-based movement (either villages, towns or cities) that envisions people working together to find ways to live with a lot less reliance on fossil fuels and on over-exploitation of other planetary resources, much reduced carbon emissions and improved wellbeing for all and stronger local economies. The Transition movement is an ongoing social experiment, in which communities learn from each other, nurturing social innovations different from the capitalistic market ethos. https://transitionnetwork.org/

Community-Supported Agriculture

A recent report by the European Community-Supported Agriculture Research Group determined that this citizen-led network of food innovation and social learning is growing steadily since it was first started in 1978 in Switzerland. Although official figures are still fuzzy or lacking in most countries, initial estimates posit that more than 1 million eaters are purchasing food in the more than 6300 initiatives distributed across Europe (European CSA Research Group, 2016). This civic partnerships between engaged customers and food producers, whereby production risks are shared between both stakeholders of the food chain, can be complemented with other types of alternative food networks and short food supply chains[20] (such as the food buying groups, solidarity purchasing groups or local food systems).

Other examples of Rural/Urban Commons that embrace food sovereignty, agroecology and the development of material and social base for a community-based solidarity economy are:

- Xarxa de Economia Solidária de Catalunya/ Fira FESC:http://www.firaesc.org/

- Genuino Clandestino (Italy) – Rural Commons, Agroecology, Food Sovereignity, Participatory Certification System (Producers/Consumers): http://genuinoclandestino.it/

- Cooperativa Integral Catalana: http://cooperativa.cat/en/4390-2/

Regarding Belgium, several types of place-based initiatives on food production and consumptions are growing exponentially, adopting different institutional forms such as community supported agriculture, food basket schemes, do-it-yourself vegetable gardens or shareholder’s cooperatives. People join those collective actions to answer perceived personal and societal needs and challenges, such as healthy and meaningful food, local and sustainable production, reducing food waste, mitigating climate change and reinforcing local bonds of conviviality (Van Gameren et al., 2015).

5.- RELATEDNESS TO OTHER COMMONS

Food production is related to other material and non-material commons that are facing similar problems of enclosure, privatization and absolute commodification such as knowledge commons (IP rights, scientific knowledge produced by companies and privately-funded research produced by universities, traditional knowledge of indigenous communities and bio-piracy, knowledge included in genetic resources, cooking recipes, etc) and material food-producing commons (land, traditional seeds and land-races, water). So, some authors already defend the whole food system should be considered as a commons, due to the essentiality of food to human survival and the importance of those systems to the planetary health (Ferrando, 2016; Lundgren, 2016).

Food-related elements that are already considered as commons

Policy makers and academics are moving from the stringent economic definition of public/private goods to a looser but more practical definition of the so-called Global Public Goods, those goods to be provided to society as a whole as they are on every body’s interest. Many food-related aspects are already considered, to a certain extent, common goods, while others are quite contested (wild foods and water) or generally regarded as private goods (cultivated food).

KNOWLEDGE COMMONS

a.- Traditional agricultural knowledge: a commons-based patent-free knowledge that would contribute to global food security by upscaling and networking grassroots innovations for sustainable and low cost food production and distribution (Brush, 2005).

b.- Modern science-based agricultural knowledge produced by public national and international institutions: Universities, national agricultural research institutes or international CGIAR, UN or EU centres, they all produce public science, widely considered as a global public good (Gardner and Lesser, 2003). More research funds shall be invested in sustainable practices and agro-ecology knowledge developed by those universities and research centres instead of further subsidizing industrial agriculture.

c.- Cuisine, recipes and national gastronomy: Food, cooking and eating habits are inherently part of our culture, inasmuch as language and birthplace, and gastronomy is also regarded as a creative accomplishment of humankind, equalling literature, music or architecture. Recipes are a superb example of commons in action and creativity and innovation are still dominant in this copyright-free domain of human activity (Barrere et al., 2012; Harper and Faccioli, 2009). It is worth mentioning this culinary and convivial commons dimension of food has received little systematic attention by the food sovereignty movements (Edelman, 2013), although it is being properly valued by alternative food networks (Sumner et al., 2010; The Food Commons, 2011).

d.- Food Safety considerations: Epidemic disease knowledge and control mechanisms are amply considered as global public goods, as zoonotic pandemics are a public bads with no borders (Richards et al., 2009; Unnevehr, 2006). Those issues are already governed through a try-centric system of private sector self-regulating efforts, governmental legal frameworks and international institutional innovations such as the Codex Alimentarius.

e.- Food price stability: Extreme food price fluctuations in global and national markets, as the world has just experienced in 2008 and 2011, are a public bad that benefits none but a few traders and brokers. Those acting inside the global food market have no incentive to supply the good or avoid the bad, so there is a need of concerted action by the states to provide such public good (Timmer, 2011).

f.- Nutrition, including hunger and obesity imbalances: There is a growing consensus that health and good nutrition should be considered as a Global Public Good (Chen et al., 1999), with global food security recently joining that debate in international fora (Page, 2013).

NATURAL COMMONS

a.- Edible plants and animals produced by nature (fish stocks and wild fruits and animals): Nature is largely a global public good (i.e. Antarctica or the deep ocean) so the natural resources shall also be public goods, although it varies depending on the proprietary rights schemes applied in each country. Fish stocks in deep sea and coastal areas are both considered common goods (Bene et al., 2011; Christy and Scott, 1965).

b.- Genetic resources for food and agriculture: Agro-biodiversity is a whole continuum of wild to domesticated diversity that is important to people’s livelihood and therefore they are considered as a global commons (Halewood et al., 2013). It should be mostly patent-free to promote and enable innovation. Seed exchange schemes are considered networked-knowledge goods with non-exclusive access and use conditions, produced and consumed by communities.

6.- RELEVANCE TO EUROPE AND EU AUTHORITIES

No food-producing common lands mentioned in CAP

The Common Agriculture Policy (CAP), what represents 40% of EU budget (52 billion Euro in 2014) is shaped by the capitalism ideology of commodification, profit-maximisation and individualism, being thus the main facilitator of the enclosure of the food commons and the restructuring of food systems, by discouraging small farming and difficulting access to land for them. The Common Agricultural Policy is closely related to managing the commons-based food producing systems and the final output (food for feeding people or other uses), but it fails to recognize the commons nature of food-producing elements such as land, seeds, water and knowledge and, least to say, food as a commons.

Although the CAP does not directly prevent common land farmers from receiving payments, it is single-farmer oriented and was not designed with common tenure in mind. Common Lands (and right to Food) is not even mentioned in CAP regulations. Common lands can only receive funds from the CAP Pillar 2 (with 20% of funds only), whereas the majority of CAP money (80%) is spent on direct payments and market measures benefiting industrial agriculture and agri-food corporations. In the EU, just three per cent of landowners have come to control half of European farmed land[21]. Those bigger farmers are the greatest beneficiaries of CAP subsidies, with 20% of farmers estimated to receive 74% of funding[22].

The impacts of EU policies on agriculture, fisheries, natural resources (land, water), biodiversity (including seeds) and traditional knowledge (including cultural heritage) are generally detrimental to the common lands, the material and immaterial commons and the commoning practices of governance.

Relevant support to food commons systems comes from:

- Urban food policies and strategies to enhance the availability of healthy and sustainable foods in metropolitan regions (Kneafsey et al., 2013)

- At EU level, this kind of initiatives benefit from Rural Development funding, within the CAP 2 Pillar or European Fund for Rural Development. LEADER programmes – through Local Action Groups - involve many local food initiative. The new proposal for CAP reform “CAP towards 2020”[23] incorporates that short supply chains may be subject to thematic sub-programmes within Rural Development programmes (Kneafsey et al., 2013).

At present, there is a consultation on the European Pillar of Social Rights (EPSR)[24]. Out of the ten topics that are considered relevant to the domain “Adequate and sustainable social protection”[25], none refer to the basic protection of two vital human rights, the right to food and the right to water, because they are considered as commodities (to be provided through the market and accessed through purchasing power) instead of public goods, rights or commons (to be provided through a polycentric governing system formed by public provision, market access and collective actions). Needless to say, the right to land or the right to have breathable air are also absent from this debate.

7.- THE TRANSITION PATHWAY FOR THE FOOD COMMONS IN EUROPE: TRICENTRIC GOVERNANCE OF THE FOOD SYSTEM

Local transitions towards the organisation of local, sustainable food production and consumption are taking place today across Europe. Directed on principles along the lines of Elinor Ostrom’s (1990, 2009) polycentric governance, food is being produced, consumed and distributed by agreements and initiatives formed by state institutions, private producers and companies, together with self-organised groups under self-negotiated rules that tend to have a commoning function by enabling access and promoting food in all its dimensions through a multiplicity of open structures and peer-to-peer practices aimed at sharing and co-producing food-related knowledge and items. The combined failure of state fundamentalism (in 1989) and so-called ‘free market’ ideology (in 2008), coupled with the emergence of these practices of the commons, has put this tricentric mode of governance back on the agenda. The further development of tricentric governance will comprise (combinations of) civic collective actions for food, the state and private enterprise.

(a) Civic collective actions for food governing food as a commons

Civic food networks are generally undertaken at local level and aim to preserve and regenerate the commons that are important for the community (food as a commons). There have been two streams of civic collective actions for food running in parallel: (a) the challenging innovations taking place in rural areas, led by small-scale, close-to-nature food producers, increasingly brought together under the food sovereignty umbrella, and (b) the AFNs exploding in urban and peri-urban areas, led on the one hand, by concerned food consumers who want to reduce their food footprint, produce (some of) their own food, improve the quality of their diets and free themselves from corporate-retail control, and on the other by the urban poor and migrants motivated by a combination of economic necessity and cultural attachments. Over the last 20 years, these two transition paths have been growing in parallel but disconnected ways, divided by geographical and social boundaries. But the maturity of their technical and political proposals and reconstruction of rururban connections have paved the way for a convergence of interests, goals and struggles. Large-scale societal change requires broad, cross-sector coordination. It is to be expected that the food sovereignty movement and the AFNs will continue (and need) to grow together, beyond individual organisations, to knit a new (more finely meshed and wider) food commons capable of confronting the industrial food system for the common good.

(b) The Partner State governing food as a public good

The state has as its main goals the maximisation of the well-being of its citizens and will need to provide an enabling framework for the commons. The transition towards a food commons regime will need a different kind of state (national states and EU authorities), with different duties and skills to steer that transition. The desirable functions are shaped by partnering and innovation rather than command-and-control via policies, subsidies, regulations and the use of force. This enabling state would be in line with Karl Polanyi’s (1944) theory of its role as shaper and creator of markets and facilitator for civic collective actions to flourish. This state has been called Partner State (Kostakis & Bauwens, 2014) and Entrepreneurial State (Mazzucato, 2013). The partner state has public authorities as playing a sustaining role (enabling and empowering) in the direct creation by civil society of common value for the common good. Unlike the Leviathan paradigm of top-down enforcement, this type of state sustains and promotes commons-based peer-to-peer production. Amongst the duties of the partner state, HELFRICH Silke mentioned the prevention of enclosures, triggering of the production/construction of new commons, co-management of complex resource systems that are not limited to local boundaries or specific communities, oversight of rules and charts, care for the commons (as mediator or judge) and initiator or provider of incentives and enabling legal frameworks for commoners governing their commons. The entrepreneurial state, meanwhile, fosters and funds social and technical innovations that benefit humanity as public ideas that shape markets (such as, in recent years, the Internet, Wi-Fi, GPS), funding the scaling up of sustainable consumption (like the Big Lottery Fund supporting innovative community food enterprises that are driving a sustainable food transition in UK) and developing open material and non-material resources (knowledge) for the common good of human societies. Public authorities will need to play a leading role in support of existing commons and the creation of new commons for their societal value.

(c) The non-profit maximiser Private Sector

The private sector presents a wide array of entrepreneurial institutions, encompassing family farming with just a few employees (FAO, 2014), for-profit social enterprises engaged in commercial activities for the common good with limited dividend distribution (Defourny & Nyssens, 2006) and transnational, ‘too-big-to-fail’ corporations that exert near-monopolistic hegemony on large segments of the global food supply chain (van der Ploeg, 2010). The latter are owned by unknown (or difficult to track) shareholders whose main goal is primarily geared to maximize their (short-term) dividends rather than equitably produce and distribute sufficient, healthy, and culturally appropriate food to the people everywhere. During the second half of the twentieth century, the transnational food corporations have been winning market share and dominance in the food chain, although space, customers and influence is being re-gained, spurred by consumer attitudes towards corporate foods and the sufficiently competitive (including attractive) entrepreneurial features of family farming (which still feeds 70% of the world’s population) and other, more socially-embedded forms of production, such as social enterprises and co-operatives. The challenge for the private sector, therefore, is to adjust direction, to be driven by a different ethos while making profit – keeping, indeed, an entrepreneurial spirit, but focusing also much more on social aims and satisfying needs. Or, put the other way around, the private sector role within this tricentric governance will operate primarily to satisfy the food needs unmet by collective actions and state guarantees, and the market will be seen as a means towards an end (wellbeing, happiness, social good) with a primacy of labour and natural resources over capital. Thus, this food commons transition does not rule out markets as one of several mechanisms for food distribution, but does it reject market hegemony over our food supplies since other sources are available, a rejection that will follow from a popular programme for provisioning of and through the food commons (popular in the sense that it must be democratically based on a generalised public perception of its goodness and efficacy).

According to the typology developed by Harvey et al. (2001), food can be provided by four types of agencies, based on different principles:

- market (based on demand-supply market rules),

- state (based on citizen rights or entitlements),

- communal (based on reciprocal obligations and norms) and

- domestic (do-it-yourself or household provision based on family obligations).

By encouraging (politically and financially) the development of non-market modes of food provisioning (state and/or communal) and (similarly, in parallel) limiting the influence of market provisioning, we can re-build a more balanced tricentric food system (Boulanger, 2010). In plain words, governments will support private initiatives whose driving force is not shareholder value maximization (e.g. family farming, food co-operatives, producer-consumer associations), while citizen/consumers will exert their consumer sovereignty by prioritising food with a meaning (local, organic, fair, healthy) beyond the purely financial (not just the cheapest). The private sector will also, or primarily (depending on the details of any particular tricentric mix), trade undersupplied, specialised and gourmet foodstuffs (food as a private good) and it may also rent commonly-owned natural resources to produce food for the market. Enterprises will further emerge around the commons that create added value to operate in the marketplace, but should probably also support the maintenance and expansion of the commons they rely on.

The transition period for this regime and paradigm shift should be expected to last for several decades, a period where we will witness a range of evolving hybrid management systems for food similar to those already working for universal health/education systems. The era of a homogenized, one-size-fits-all global food system will be replaced by a diversified network of regional foodsheds designed to meet local needs and re-instate culture and values back into our food system (The Food Commons, 2011). The Big Food corporations will not, of course, allow their power to be quietly diminished, and they will, inevitably, fight back by keep on doing what has enabled them to reach such a dominant position today: legally (and illegally) lobbying governments to lower corporate tax rates and raise business subsidies, mitigate restrictive legal frameworks (related to GMO labelling, TV food advertising, local seed landraces, etc.) and generally using the various powers at their disposal to counter alternative food networks and food producing systems. To emphasise, the confrontation continue over decades, basically paralleling and in some ways reversing, in fact, the industrialisation and commodification path that led us to this point.

Appropriate combinations of self-regulated collective actions, governmental rules and incentives, and private sector entrepreneurship should yield good results for food producers, consumers, the environment and society in general. The tricentric governance schemes will be initiated at both local and regional scales, as they imply a different way of organising the territory: smaller bio-regions with stronger local authorities, community-based civic collective actions and nested markets to supply unmet needs, supported by a partner and also entrepreneurial state with a better balance of command-and-control measures and reflexive governance tools. Regarding socio-economic and environmental sustainability, the governance of food as a commons will rest on three premises:

the bonds and multi-dimensional value systems of the food-producing communities,

the tricentric governance mechanisms steered by partner states that regulate the food production, distribution and consumption, and

the sustainability of the food producing systems to maintain food footprints within ecological boundaries and to produce good food economically and efficiently.

[FIchier:FoodCommons2.png|400px]]

8.- HOW THE “FOOD COMMONS” COULD BE SUPPORTED BY EU AUTHORITIES?

The consideration of food as commons and public good could unlock food policy options that have so far being dismissed just because they did not align with the dominant neoliberal narrative. If food is valued and governed as a commons in Europe, the following food policy options could be considered, first as an idea and then as normative, political, legal and financial measures.

NORMATIVE MEASURES

1.- Mirroring the successful European Citizen Initiative on water as a commons and public good, a similar initiative could be launched to consider food as a human right, a public good and a commons in European policy and legal frameworks. This does not prevent to have traded food for profit, but policy priorities should be geared towards safeguarding farmer’s livelihood and eater’s rights to adequate and healthy food.

2.- The European Parliament could elaborate a declaration where food is no longer considered as a mere commodity but declared as commons, public good and human right that shall be guaranteed to every EU citizen. This political declaration would send an important message for EU member states and it will certainly influence the coming negotiations of the Common Agricultural Policy (that could be re-named as Commons Food Policy).

3.- Set aspirational and inspirational targets for food provisioning in 2030 (for example)

- 60% private sector

- 25% self-production (collective actions)

- 15% state-provisioning (public buildings, destitute people, unemployed families) through Universal Food Coverage

POLITICAL MEASURES

4.- None of five Regulations that conform the legal/political corpus of the reformed CAP (December 2013) have included any reference to the “right to food”, “commons” and “common resources”. So, in the next CAP reform, at least some specific references to the right to food provisions (adopted by all the EU members individually when they ratified the International Covenant of Economic, Social and Cultural Rights) could be included as well as a recognition of the importance of the food-producing commons in Europe, as particular institutional arrangements where collective management of natural resources in historical institutions provides utilities in form of food products, landscape stewardship and cultural heritage. None of this regulations mention the commons or the right to food:

- Rural Development: Regulation 1305/2013[26]

- Horizontal issues such as funding and controls: Regulation 1306/2013[27]

- Direct payments for farmers: Regulation 1307/2013[28]

- Market measures: Regulation 1308/2013[29]

- To ensure a smooth transition, Regulation 1310/2013[30]

5.- School Meals shall be considered as a universal entitlement and a public health priority. This meals could form the transformative core of different EU food policies in the following form: School meals would be a universal right to all European students, either in public or private schools. Those meals in public schools should be cooked daily in the same school premises (as long as possible), using organic and seasonal products produced by local farmers (either private farmers or public servants) under agroecological systems and being free and the same to all students. A real universal entitlement that would prevent unhealthy eating habits at school, eliminate eating disparities due to class, gender and religion, and support local farming systems. Eating together healthy food would become a collective activity, governed by parents, school staff and state authorities, that would revalorise the food commons.

6.- Encourage Food Policy Councils (open membership to citizens) through participatory democracies, financial seed capital and enabling laws. Those councils could be established at local level (villages and cities), or regional and national. Once a sufficient number is achieved in all EU members, an EU Food Policy Council could be established to monitor the reform yet-to-be Commons Food Policy.

7.- Food producers could be considered a profession relevant to the public interest (or the commonwealth) and thus some farmers and fishermen could be directly employed by the State to provide food regularly to satisfy the State needs (i.e. for hospitals, schools, army, ministries, etc). A certain number of food producers could thus become public servants, as already happening at municipal level. https://magazine.laruchequiditoui.fr/profession-agriculteur-municipal/

8.- Establishing public bakeries where every citizen can get access to a bread loaf every day (if needed or willing to). That would be a mix between a symbolic movement (one piece of bread does not guarantee adequate food for all) and a first political move towards a public reclaim of the commoditised food system.

9.- Another proposal is to take the international food trade outside the World Trade Organization, as food cannot be considered like other commodities, due to its multiple dimensions for human beings. Along those lines, a different international food treaty should be crafted, whereby countries abide by and respect some minimum standards in food production and trade. It should be a binding treaty.

10.- Public-private partnerships (PPP) in the food sector are decision-making spaces for the private sector to influence policymakers in order to arrange a legal space which is conducive to profit-seeking. Since they are not meant to maximize the health and food security of the citizens but mainly to maximize profit-seeking, these PPPs should be restricted to operational arrangements but never to dealing with policy making or legal frameworks.

LEGAL MEASURES

11.- The European Parliament could prepare a non-binding communication to the EU members recommending the development at national level of appropriate legal measures to incorporate the right to food as a binding right (constitutional or with a lower level)[31].

12.- A Universal Food Coverage could be engineered to guarantee a minimum amount of food to every EU citizen, everywhere, every day, similar to universal health coverage and universal primary education, both available in different forms in all European countries. Why is what we see as acceptable for health and education so unthinkable for food? Is education more important to human development than eating? As a token, public bakeries where people could be entitled to one bread loaf every day could be a practical example on how this could work.

13.- Patenting living organisms should be banned. We can patent computers, iPods, cars, and other human-made technologies but we cannot patent living organisms such as seeds, bacteria or genetic codes. That should be an ethical minimum standard and a fundamental part of our new moral economy of sustainability. Excessive patents of life shall be reversed, applying the same principles of free software to the food domain. It seems the patents-based agricultural sector is slowing or even deterring the scaling up of agricultural and nutritional innovations and the freedom to copy actually promotes creativity rather than deter it[32], as it can be seen in the fashion industry or the computer world. Millions of people innovating on locally-adapted patent-free technologies have far more capacity to find adaptive and appropriate solutions to the global food challenge than a few thousand scientists in the laboratories and research centres (Benkler, 2006).

14.- Food speculation should be banned, because it does not contribute to improving the food system, neither food production, nor consumption, and it has many damaging collateral effects. Food can be traded, insured, and exchanged, but not speculated on.

15.- Legal lock-in regulations that prevent self-regulated collective actions for food, such as urban gardens, incredible edible, meal exchange systems, farmer’s markets, seeds and food exchange mechanisms, should be reformed, and a higher role for non-market & non-state self-regulated collective actions should be allowed (more funds, protective legal space for collective decisions at local level). For instance, allow exchange/trade of local seed varieties, increase governmental purchase of food from local, organic sources, levy food safety regulations that only favour corporate food

16.- Stricter & innovative rules to avoid food waste, such as binding regulations to recycle all expired food (i.e. France) or supporting citizens´ collective actions to reduced waste, promote food sharing and c5-producing

17.- All agricultural research funded with public funds shall be automatically granted the IP right of open knowledge or public domain knowledge.

FINANCIAL MEASURES

18.- Food-related subsidies at EU level shall be re-considered in order to support those innovative civic actions for food that are mushrooming all over Europe: “Territories of Commons”, community-supported agriculture, food buying groups, open agricultural knowledge, urban food commons, peer-to-peer food production. This area of the European food system shall be recognized by politicians and local/national and EU authorities and be granted legitimacy and financial/legal support.

19.- Shifting from charitable food (Food Banks supported by humanitarian assistance funds from the CAP) to food as right (Universal Food Coverage for all). The EP could elaborate a communication to revisit the growing number of food banks in Europe and call for an EU food bank network that is universal, accountable, compulsory and not voluntary, random and targeted.

Additional references to understand the normative shift of Food as a Commons

SLIDESHARE POWERPOINTS:

1.- Europe’s Food and Agriculture in 2050

2.- Food is not a right in the SDGs: the EU position analysed http://www.slideshare.net/joseluisviveropol/food-is-not-a-right-in-the-sdgs-the-us-and-eu-positions-analysed

3.- Narratives of food transition in 2050

http://www.slideshare.net/joseluisviveropol/session-3-narratives-of-transition-to-2050

4.- Valuation of food dimensions and policy beliefs in transitional food systems. Food as a commons or commodity?

5.- The right to food: achievements, barriers and policy proposals. http://www.slideshare.net/joseluisviveropol/right-to-food-achievements-barriers-policy-proposals

6.- How to reclaim our food commons? Meaningful food to crowdfeed Europe http://www.slideshare.net/joseluisviveropol/how-to-reclaim-our-food-commons

7.- L’alimentation come bien commun: la transition alimentaire par l’action collective http://www.slideshare.net/joseluisviveropol/l-alimentation-comme-un-bien-commun-une-nouvelle-paradigm

OUTREACH PUBLICATIONS FOR A BROADER AUDIENCE

1.- Seeing food as a commons:

http://blog.p2pfoundation.net/seeing-food-as-a-commons/2013/10/07

2.- The Food Commons Transition Commons Transition Wiki http://wiki.commonstransition.org/wiki/The_Food_Commons_Transition:_Collective_actions_for_food_and_nutrition_security

3.- Food as a commons: A shift we need to disrupt the neoliberal food paradigm. Heathwood Institute and Press. Critical theory for radical democratic alternatives. June 2015

4.- Can we end hunger in the post-2015 frame with food as a commodity?

CTA Knowledge for Development Blog. February 2016. http://knowledge.cta.int/Dossiers/S-T-Issues/Food-security/Feature-articles/Can-we-end-hunger-in-the-post-2015-frame-with-food-as-a-commodity

5.- Food is a global public good and a commons

ENTITLE Blog: a collaborative writing project on political ecology.

https://entitleblog.org/2016/03/03/food-is-a-global-public-good-and-a-commons/

6.- Why food should be a commons and not a commodity Shareable, 9 October 2013

http://www.shareable.net/blog/why-food-should-be-a-commons-not-a-commodity

7.- Staying alive shouldn’t depend on your purchasing power. OP-ED article in The Conversation (12 December 2013). https://theconversation.com/staying-alive-shouldnt-depend-on-your-purchasing-power-20807

8.- The Food Commons transition. Collective actions for food security. OP-ED Article in The Broker Magazine (22 January 2014). http://thebrokeronline.eu/Articles/The-food-commons-transition

9.- Why isn’t food a public good?

Policy Innovations Blog, Carnegie Council for Ethics in International Affairs, 11 September 2014

http://www.policyinnovations.org/ideas/commentary/data/00289

http://www.globalpolicyjournal.com/blog/01/10/2014/why-isnt-food-public-good

10.- Crowdfeeding the world with meaningful food: food as a commons

Brighton and Sussex Universities Food Network. 16 February 2015

11.- De-commodifying Food: the last frontier in the civic claim of the commons

Landscapes for people, food and nature Blog. 2 March 2015.

ACADEMIC PUBLICATIONS

1.- The food commons transition : collective actions for food and nutrition security. In: Ruivenkamp, G. & A. Hilton (eds.). Autonomism and Perspectives on Commoning. Zed Books. (forthcoming, 2017).

2.- No right to food and nutrition in the SDGs: mistake or success? BMJ Global Health 1(1) e000040; DOI: 10.1136/bmjgh-2016-000040 (2016). http://gh.bmj.com/content/1/1/e000040

3.- Entender la alimentación como un bien común. Soberanía Alimentaria, Biodiversidad y Culturas #23 (in spanish). (2016) http://www.soberaniaalimentaria.info/numeros-publicados/54-numero-23/315-entender-la-alimentacion-como-un-bien-comun

4.- Transition Towards a Food Commons Regime: Re-Commoning Food to Crowd-Feed the World. Social Science Research Network. (2015)

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2548928

5.- Food is a public good. World Nutrition 6, 4: 306-309. (2015) https://www.researchgate.net/publication/274377117_Food_is_a_public_good

6.- What if food is considered a common good? UNSCN News 40: 85-89. United Nations Standing Committee on Nutrition, Geneve. (2014) http://www.unscn.org/en/publications/scn_news/

7.- Los alimentos como un bien común y la soberanía alimentaria: una posible narrativa para un sistema alimentario más justo. In X. Erazo, R. Méndez, L.E. Monterroso & C. Siu eds. Seguridad alimentaria, derecho a la alimentación y políticas públicas contra el hambre en América Central. Pp. 27-44. Editorial LOM, Santiago, Chile (2014)

8.- Food as a commons: reframing the narrative of the food system. Social Science Research Network. (2013) http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2255447

9.- Soberanía alimentaria y alimentos como un bien común. En: Seguridad Alimentaria: derecho y necesidad. Dossier 10 (Julio): pp 11-15. Economistas Sin Fronteras, Spain. (2013)

http://www.ecosfron.org/portfolio/seguridad-alimentaria-derecho-y-necesidad/#.Uh3BAfW3vbk

- ↑ Universite catholique of Louvain, Belgium Email: [[../customXml/item1.xml|jose-luis.viveropol@uclouvain.be]]

- ↑ Indigenous peoples’ and Conserved Community territories and Areas: natural areas, resources, species and habitats conserved in a voluntary, common and self-directed way by local communities and indigenous peoples throughout the world http://www.iccaconsortium.org/

- ↑ The Global Subsidies Initiative http://www.iisd.org/gsi/ [Accessed January 7 2014].

- ↑ The average support to agricultural farmers in OECD countries in 2005 reached 30% of total agricultural production, equalling to 1 billion $ per day (UNCTAD, 2013). In OECD countries, agricultural subsidies amount $400 billion per year. Moreover, the world is spending half a trillion dollars on fossil fuel subsidies every year. The overall estimate for EU biofuels subsidies in 2011 was €5.5–€6.8 billion (IISD, 2013; WWF, 2011).

- ↑ http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/Common_land_statistics_-_background

- ↑ Legislation in Finland (www.ym.fi/publications )

- ↑ A good and well-known example is the 500 practising commoners in the New Forest, Hampshire.

- ↑ The Countryside and Rights of Way Act 2000 gave the public the right to roam freely on registered common land in England

- ↑ http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20130123162956/http://www.defra.gov.uk/wildlife-countryside/protected-areas/common-land/about.htm

- ↑ Author’s estimate based on previous data. Northen Ireland has not been included in this estimate.

- ↑ Those who have “open house and a burning fireplace” what means they regularly inhabit that house, either owned or rented. Therefore, commonality, as a proprietary entitlement to use common resources, is not inherited but granted by living in the community.

- ↑ There are 2800 Montes Vecinales de Mano Comun (Collectively-Owned Community Forests) legally protected, representing a third of total forest area. They produce wood, food, pasturelands, income by selling wood or renting land for wind-power turbines. They are an example of direct assembly democracy that can be replicated on other settings applying the EU's principle of subsidiarity in decision-making. More info at: http://montenoso.net/wiki/index.php/MVMC/es

- ↑ Law 13/1989 (10 October) de Montes Vecinales en Man Común (DOG nº 202, 20-10-1989) and Law 7/2012 (28 June) de montes de Galicia.

- ↑ The term “Università” derives from the ancient roman term “Universitas Rerum” (Plurality of goods) while the term “Agraria” refers to the rural area. http://www.agrariasacrofano.it/Storia.aspx

- ↑ The same can be said of community-managed forests worldwide (Porter-Bolland et al., 2012).

- ↑ ECOLISE http://gen-europe.org/partners/ecolise/index.htm

- ↑ Transition Network https://transitionnetwork.org/

- ↑ http://gen-europe.org/home/home/index.htm

- ↑ http://gen-europe.org/partners/ecolise/index.htm

- ↑ Short food supply chains are defined by Kneafsey et al., (2013) as: “Those initiatives where the food involved are identified by, and traceable to a farmer. The number of intermediaries between farmer and consumer should be ‘minimal’ or ideally nil.”

- ↑ See Land concentration, land grabbing and people’s struggles in Europe at http://www.tni.org/briefing/land-concentration-land-grabbing-and-peoples-struggles-europe-0

- ↑ EU Agricultural Economics Briefs No 8 | July 2013. How many people work in agriculture in the European Union? An answer based on Eurostat data sources http://www.ecpa.eu/information-page/agriculture-today/common-agricultural-policy-cap

- ↑ See COM(2011) 627 final/2 (article 8, page 34)

- ↑ http://ec.europa.eu/priorities/deeper-and-fairer-economic-and-monetary-union/towards-european-pillar-social-rights_en

- ↑ http://ec.europa.eu/priorities/adequate-and-sustainable-social-protection_en

- ↑ REGULATION (EU) No 1305/2013 on support for rural development by the European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development (EAFRD) and repealing Council Regulation (EC) No 1698/2005 http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32013R1305&from=en

- ↑ REGULATION (EU) No 1306/2013 on the financing, management and monitoring of the common agricultural policy http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32013R1306&from=en

- ↑ REGULATION (EU) No 1307/2013 establishing rules for direct payments to farmers under support schemes within the framework of the common agricultural policy http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32013R1307&from=en

- ↑ REGULATION (EU) No 1308/2013 establishing a common organisation of the markets in agricultural products http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32013R1308&from=en

- ↑ REGULATION (EU) No 1310/2013 laying down certain transitional provisions on support for rural development by the European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development (EAFRD), http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32013R1310&from=en

- ↑ See a recent debate on that topic: http://www.milanfoodlaw.org/?p=5509&lang=en

- ↑ The Economist (2014, 2015) http://www.economist.com/blogs/freeexchange/2014/08/innovation and http://www.economist.com/news/leaders/21660522-ideas-fuel-economy-todays-patent-systems-are-rotten-way-rewarding-them-time-fix